|

Inside And Outside Of Vietnam

- .22’s And 52’s -

Reconnaissence Operations And Ingenious Viet Cong & North Vietnamese Army Early Warning Systems

Compiled by John McCarthy

The Viet Cong (VC) and the North Vietnamese Army (NVA) always knew when the B-52’s were coming.

We had

to find out how.

The Missions:

Those who served in South Vietnam know that Strategic Force B-52 bombers were used intensively within South Vietnam

in support of Military Assistance Command Vietnam (MACV) tactical objectives. The iron bomb strikes were used both on pre-planned

missions and on targets of opportunity and were collectively named Arc Light missions. The bombers flew from bases both on

Guam and Okinawa and each B-52 was capable of carrying 110 bombs of the 750 pound category. The missions were invariably flown

at altitudes above 30,000 feet where the planes were virtually unseen from the ground and inaudible to the naked ear. A network

of ground control radar installations using a technique that was named Sky Spot was capable of bringing US air power to bear

anywhere in South Vietnam with a very high degree of accuracy. A single B-52 put down a carpet of bombs approximately 600

meters wide by 1000 meters in length literally obliterating everything on the ground within that area.

Compromise:

It was also widely known that many Arc Light missions were compromised in some fashion – the troop concentrations,

their primary objectives, were simply gone from the target areas by the time the bombs were dropped and detonated.

Manipulation:

Almost invariably, Bomb Damage Assessment (BDA) ground-reconnaissance missions were inserted into the target areas to determine

success or failure of Arc Light missions and almost invariably they found few if any casualties in the target areas throughout

the entire war.

What Really Happened:

There were many theories for the compromises ranging from the necessity to “clear” pre-planned missions with

South Vietnamese Government officials (down to the province level) to the presence of Russian trawlers off Guam and Okinawa

that supposedly reported the departure of B-52 missions for Southeast Asia. These theories, however, did not account for the

ineffectiveness of “target of opportunity” missions where B-52’s in the air en route to pre-planned objectives

were diverted in flight and on short notice dropped their loads on targets that were under the observation of Forward Air

Controllers (FAC’s) working with U.S. forces on the ground.

Information gathered years after the war provided insight to the real potential for espionage by the infiltration of penetration

agents trained by the KGB, the Soviet Unions version of the CIA. The actual landing site map coordinates of pre-planned bombing

targets were transmitted by radio code prior to bombing missions. The National Security Agency, NSA, intercepted

and decoded these transmissions. The Air Force would communicate the target coordinates to the Military Assistance Command

Vietnam, MACV, therefore it was concluded that the internal security of MACV was compromised by penetration agents who had

access to this important information. The MACVSOG missions were also compromised by the transmission of their landing sites

inside Cambodia and Laos before they launched from their launch bases. Virtually all of the OP34-Alpha small commando teams,

whose number totaled more than 700, were either killed or captured upon landing during commando raids on North Vietnam. This

did not deter the launch of more teams. Only 286 survived as much as 21 years confinement in North Vietnamese Prisons. The

CIA and MACVSOG declared these men dead to cut off the stipend the families were contracted to receive in the event of capture.

The inception of intelligence missions into the North was fathered by the Central Intelligence Agency, primarily under

William Colby when he was Station Chief in Saigon. The operation aimed at penetrating through two specific mediums the air

and water. Conceived along the lines of the World War II's Office of Strategic Services (OSS) teams, groups operating behind

the lines was an attractive idea. Past penetration operations in Europe, in Korea during the Korean War, and others into China

had failed; however, the hopes here were that these would be successful. Small, well-trained groups or teams were either dropped

into the North by air, sometimes using Taiwanese aircrews, or were delivered along the extensive North Vietnamese coastline.

The purpose was to acquire information about the North's activities and to develop the network's capable of disrupting the

North's covert operations and later main drives into the South.

The program was a massive failure. Station Chief Colby came to the conclusion that these groups were being quickly captured

by the internal security forces in the North and the information that was coming through was "disinformation" originating

from Communist sources who were now controlling the teams. There were suspicions of leaks and the growing belief in the quality

of counterintelligence in the North as being supreme in the game to gather intelligence on the ground. When the OP34A was

taken over by the Department of Defense (DOD), Station Chief Colby told Secretary Robert McNamara that the program was not

working and the groups had been easily "rolled up" by the North. The information that was received was very questionable.

Still, DOD continued until variations on OP34A showed the futility of it all. The prisons were becoming full of the operatives.

The North kept the fact that it was holding these POWs from the Americans, who never acknowledged the fact that operations

in the North had been compromised. Even after the North's entry into Saigon, few knew of the continued imprisonment. Families,

if told anything at all, were told their men had probably died. The American press has picked up this aspect of death notification

and then highlighted the family discovering a loved one still alive. The press condemned DOD for the problem and spared the

North any blame. –Tourison: Secret Army, Secret War

Many South Vietnamese families refused to accept the fact that after 21 years their loved ones were returned, alive. They

initially thought they were ghosts and refused to allow them back into their families.

In late 1972, as the Paris peace talks convened, clothing and food improved for the captured commandos. Word spread among

them that all prisoners of war would be released under the emerging treaty. On Jan. 27, 1973, the cease-fire agreement was

signed by the United States, South Vietnam and North Vietnam, calling for the return of prisoners of war within 60 days. Although

almost 600 U.S. POWs were released, the commandos - some of whom had been in the same prisons as the Americans - were not.

In protest, scores of them staged a series of hunger strikes that were mercilessly broken up by prison guards armed with clubs

and dogs.

At the negotiating table in Paris, the United States might not have been in any position to ask for the release of the

commandos. "How could you ask for them?" Andrade asks. "These were not supposed to be United States teams, and you would not

want to disclose your collusion in a secret operation. Even if we were involved in the training and the missions, it was (South

Vietnamese) President Nguyen Van Thieu's job to ask for them."

While working as the Operations Officer (S-3) of Project Omega, in August, 1967, a 1000 man 5th Special Forces Group reconnaissance

force in direct support of the U.S. I Force Vietnam (I FORCE V), commanded by four star General William B. Rosson, who was

also a full time agent of the CIA (whom I directly briefed on the updates of Omega operations rather than the HQ 5th Special

Forces which was also located in Nha Trang, Vietnam), I had occasion to divert an Arc Light mission to a hot target. In the

course of doing a Bomb Damage Assessment, BDA, on the target we discovered (1) the strike was ineffective and (2) why.

Nha Trang, South Vietnam

This is the story of the events leading up to the discovery of the target, the bomb attack on the target, and the startling

and innovative North Vietnamese counter to the potentially devastating effects of massive American air power.

The 5th Special Forces Civilian Irregular Defense Group Camp (CIDG) – established in 1961 by the CIA as an “off

the shelf”, private army numbering some 85,000 men, each armed with mostly WWII automatic weapons which were in abundant

supply from the CIA storage facilities on Okinawa. The CIDG program was the dream child of the CIA who continued to fund their

operations and saleries after they were turned over to Special Forces control in 1963. One such camp was established

at Plei Djereng and lay west of Pleiku thirty miles and north of old Route 19 and was a border surveillance camp that kept

watch on the part of the Ho Chi Minh Trail that swept south through Laos and Cambodia and into the South Vietnamese Highland

Plateau.

By 1966, there were 100 Special Forces Camps, most along the Cambodian and Laotian border, each with over 600 CIDG trained

forces. Each man was a ‘trigger puller’. This force did not consist of cooks, bottle washers, truck drivers, and

other support personnel. Each was a rifleman carrying what was required to sustain him on his back. When deployed, these units

were re-supplied by air drop. Additionally, there were numerous Mike Force Companies of 300 each dispersed throughout the

country, normally adjacent to major CIDG strongholds, which were used as reactionary forces to provide relief support for

any Special Forces camp under attack and would be deployed by helicopter or by parachute, depending on the location and battle

conditions. Occasionally, the Mike Force companies were called in to support conventional U.S. forces under attack or used

as a blocking force for a conventional force action.

Having an 85,000 man force under the command of an Army Colonel didn’t sit well with regular Army Generals or their

subordinates who were lucky to command a U.S Army Division with 11,000 men, over half of which were support personnel as opposed

to combat units.

During the Vietnam War, there were eleven support personnel for every Combat Infantryman. In 1966, the US Armed

Forces in Vietnam numbered 500,000 which equates to only 45,000 U.S combat riflemen for the entire country of South Vietnam

at any one time. This fact of life had no bearing on those who were killed or wounded while acting in their support roles

and the overall effectiveness of military action in Vietnam which would not have been possible without them and their service.

Project Omega, though a self contained reconnaissance force of 1000 riflemen, was frequently satellited on CIDG camps in

the conduct of its far roving reconnaissance as all came under the overall command of 5th Special Forces Group and specifically

of Company “B” of the organization located in Pleiku. Omega’s three rifle companies, of 300+ men each, were

from the Jerai Tribe of the Montagnard hill people of the Central Highlands area of Vietnam. All were members of the Fulro

Movement, a political organization which coordinated the activities of the major Montagnard Tribes: The Montagnards constitute

one of the largest minority groups in Vietnam. The term Montagnard, loosely used, like the word Indian, applies to more than

a hundred tribes of primitive mountain people, numbering from 600,000 to a million and spread over all of Indochina. In South

Vietnam there are some twenty-nine tribes, all told more than 200,000 people. Even within the same tribe, cultural patterns

and linguistic characteristics can vary considerably from village to village. In spite of their dissimilarities, however,

the Montagnards have many common features that distinguish them from the Vietnamese who inhabit the lowlands. The Montagnard

tribal society is centered on the village and the people depend largely on slash-and-burn agriculture for their livelihood.

Montagnards have in common an ingrained hostility toward the Vietnamese and a desire to be independent.

Throughout the course of the French Indochina War, the Viet Minh worked to win the Montagnards to their side. Living in

the highlands, these mountain people had been long isolated by both geographic and economic conditions from the developed

areas of Vietnam, and they occupied territory of strategic value to an insurgent movement. The French also enlisted and trained

Montagnards as soldiers, and many fought on their side.

There were two principal reasons for the creation of the Civilian Irregular Defense Group program. One was that the U.S.

Mission in Saigon, the CIA, believed that a paramilitary force should be developed from the minority groups of South Vietnam

in order to strengthen and broaden the counterinsurgency effort of the Vietnamese government. The other was that the Montagnards

and other minority groups were prime targets for Communist propaganda, partly because of their dissatisfaction with the Vietnamese

government, and it was important to prevent the Viet Cong from recruiting them and taking complete control of their large

and strategic land holdings.

One major study of the situation in Southeast Asia concluded that in 1961 the danger of Viet Cong domination of the entire

highlands of South Vietnam was very real, that the efforts of the Vietnamese Army to secure the highlands against Viet Cong

infiltration were ineffective, and that the natural buffer zone presented by the highland geography and Montagnard population

was not being utilized properly to prevent Communist exploitation. The government was, in fact, failing to exercise any sovereignty

over its highland frontiers or its remote lowland districts in the Mekong Delta where other ethnic and religious minority

groups were established. This lack of control deprived the government of any early intelligence of enemy attacks and any real

estimate of Viet Cong infiltration. The Communists, on the other hand, continued to exploit the buffer zone, and there was

always the danger that the insurgents would use this territory as a springboard into the more heavily populated areas.

The Vietnamese had not only made no attempt to gain the support of the Montagnards and other minority groups but in the

past had actually antagonized them. Before 1954 very few Vietnamese lived in the highlands. In that year some 80,000 refugees

from North Vietnam were resettled in the Montagnard area, and inevitably friction developed. Dissatisfaction among the Montagnards

reached a point where in 1958 one of the principal tribes, the Rhade, organized a passive march in protest. Vietnamese officials

countered by confiscating the tribesmen's crossbows and spears, an act that further alienated the Montagnards.

The indifference of the Vietnamese to the needs and feelings of the tribesmen grew directly out of their attitude toward

the Montagnards, whom the Vietnamese had traditionally regarded as an inferior people, calling them "moi," or savages, and

begrudging them their tribal lands. This attitude on the part of the Vietnamese plagued the Civilian Irregular Defense Group

program from the beginning. Not until 1966 did the Vietnamese, in their desire to bring the tribes under government control,

begin to refer to the Montagnards as Dong Bao Throng, "compatriots of the highlands." Even so, the animosity between Montagnards

and Vietnamese continued to be a major problem.

The term Montagnard means "mountain people" in French and is a carryover from the French colonial period in Vietnam.

The term is preferable to the derogatory Vietnamese term moi, meaning "savage." Montagnard is the term, typically shortened

to Yard, used by U.S. military personnel in the Central Highlands during the Vietnam War. The Montagnards, who are

made up of different tribes, with many overlapping customs, social interactions, and language patterns, typically refer to

themselves by their tribal names such as Jarai, Koho, Manong, and Rhade. Physically, the Montagnards are darker skinned than

the mainstream Vietnamese and do not have epicanthic folds around their eyes. In general, they are about the same size as

the mainstream Vietnamese. Altogether, more than 30,000 Montagnard tribal members were armed and trained as an effective fighting

force by Special Forces during the Vietnam War.

Since the Rhade (Rah-day) tribe is fairly representative of the Montagnards, a description of the way of life of the villagers

will serve as a good example of the environment in which the Special Forces worked in Vietnam. The Rhade were, furthermore,

the first to be approached and to participate in the CIDG program. For many years, the Rhade have been considered the most

influential and strategically located of the Montagnard tribes in the highlands of Vietnam. Mainly centered around the village

of Ban Me Thuot in Darlac Province, the Rhade are also found in Quang Due, Phu Yen, and Khanh Hoa Provinces. While there are

no census records for these people, it has been estimated that the tribe numbers between 100,000 and 115,000, with 68,000

living in Ban Me Thuot.

The Rhade have lived on the high plateau for centuries, and their way of life has changed little in that time; whatever

changes came were mainly the result of their contact with the "civilized" world through the French. They settle in places

where their livelihood can be easily secured, locating their houses and rice fields near rivers and springs. Because they

have no written history, not much was known about them until their contact with the French in the early nineteenth century.

It is generally agreed that most of their ancestors migrated from greater China, while the remainder came from Tibet and Mongolia.

|

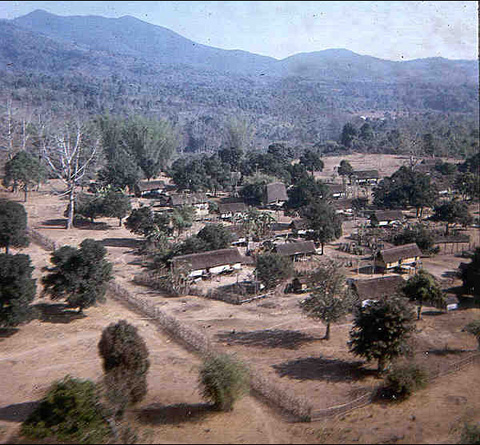

Montagnard Village

|

|

Montagnard Tribe Village Members In Central Highlands

of Vietnam

|

In order of descending importance, the social units of the Rhade are the family, the household, the kinsmen, and the village.

The Rhade have a matrilineal system; the man is the breadwinner, but all property is owned by the wife. The oldest female

owns the house and animals. The married man lives with his wife's family and is required to show great respect for his mother-in-law.

If a man is rich enough he may have more than one wife, but women may have only one husband. Marriage is proposed by the woman,

and the eldest daughter inherits her parents' property.

|

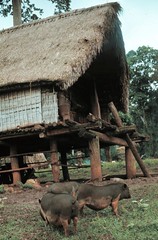

Typical “Long Houses” of Montagnard

Tribes

|

Building a house is a family enterprise. All members of families who wish to live together pitch in and build a longhouse

in accordance with the size of the families. The house is made largely of woven bamboo and is long and narrow, sometimes 400

feet long, with entrances at each end. Both family and guests may use the front entrance, but only the resident families may

use the rear. The house is built on posts with the main floor usually about four feet above the ground and is almost always

constructed with a north-south orientation, following the axis of the valleys.

|

Typical “Long Houses” of Montagnard

Tribes

|

The tasks of the man and woman of the family are the traditional ones. The man cuts trees, clears land, weaves bamboo,

fishes, hunts, builds houses, carries heavy objects, conducts business, makes coffins, buries the dead, stores rice, makes

hand tools and weapons, strikes the ceremonial gongs -an important duty- and is responsible for preparing the rice wine.

Authority in the Rhade family is maintained by the man—the father or the grandfather. It is he who makes the decisions,

consulting with his wife in most cases, and he who is responsible for seeing that his decisions are carried out. The average

Rhade man is between sixty-four and sixty-six inches tall, brown in complexion, and usually broad shouldered and very sturdy.

The men have a great deal of endurance and manual dexterity and have the reputation of being excellent runners.

The woman draws water, collects firewood, cooks the food, cleans the house, mends and washes the clothes, weaves, makes

the traditional red, black, yellow, and blue cotton cloth of the Rhade, and cares for the children. The women sit on the porch

(the bhok-gah) of the longhouse to pound the rice with a long pole and a wooden mortar.

The life of the Rhade is governed by many taboos and customs. Outsiders are expected to honor these, and therefore delicacy

was required of Special Forces troops who dealt with the Rhade and other tribes. Healing is the responsibility of the village

shaman, or witch doctor, and the general state of health among the Rhade is poor. Religion is animistic -natural objects are

thought to be inhabited by spirits- but the tribe also has a god (Ae Die) and a devil (Tang Lie).

The Rhade tend toward a migratory existence. Once they have used up the soil's vitality in one area, they move their village

to a new place, seeking virgin soil or land that has not been used for half a century. At the beginning of the rainy season

the people plant corn, squash, potatoes, cucumbers, eggplant, and bananas. Once these crops are in the ground, the rice is

planted.

The Rhade proved to be enthusiastic participants in the CIDG program in the beginning because the early projects were,

they felt, pleasing to the spirits and helpful to their villages. If these two requirements were satisfied (and in many instances

they were not later on), the Rhade, and the Montagnards in general, were quite willing to work hard in the CIDG program.

The Montagnards were not, of course, the only minority group involved in the CIDC program; other groups were Cambodians,

Nung tribesmen from the highlands of North Vietnam, and ethnic Vietnamese from the Cao Dai and Hoa Hao religious sects.

Fulro is a French acronym: Front Unifie De Lutte Des Races Opprimees. Literally translated; The United Front for

the Oppressed Races. Perhaps one of the biggest regrets of the Fulro movement occurred in 1964, when eager for official recognition,

3000 Fulro soldiers who were working with US Special Forces revolted and took over several villages, killing several South

Vietnamese soldiers in the process. Sympathetic US Special Forces soldiers volunteered to be "hostages" and negotiations soon

began between the US, South Vietnam, and the Fulro. Although a US brokered peace deal gave the Montagnards concessions from

the South Vietnamese government, (which were never fulfilled after the Khanh government was overthrown in a coup by Nguyen

Caio Ky the following year) the Fulro leadership, led by General Y-Bham Enuol, was granted amnesty but exiled to Cambodia, where they remained for the next decade. With their leadership living in exile,

the Fulro was clearly split into two arms—a political arm based in Cambodia and a militant arm working side by side

with US Special Forces soldiers. Although the movement had a new name, the goal remained the same—to win political autonomy

and freedom from oppression by the South Vietnamese Government.

Complicating the Fulro matter above, those South Vietnamese soldiers killed in the uprising in 1964, were Vietnamese Special

Forces, Luc Luong Dak Biet Vietnam, RVN, Republic of Vietnam. There was always a tense relationship between the USSF and the

VNSF as a result of this uprising.

As a “practical matter”, it was quite obvious that who ever came out as the victor between North and South

Vietnam, the Montagnard tribes would be hunted down and annihilated upon the conclusion of the war in Vietnam. The Government

of South Vietnam always referred to the Montagnard as savages, or Moi. The Democrative Republic of Vietnam, or North Vietnam,

was none too happy with the Montagnard who not only worked in concert with the American Special Forces but also with the French

in the Indo China War, 1949 to 1954.

It is noteworthy that some 80,000 North Vietnamese were brought into South Vietnam during the 1950’s and transplanted

onto the tribal lands of the Montagnard, in the Central Highlands, by the South Vietnamese Government.

Needless to

say, this was kin to throwing a match into a can of gasoline. Some Montagnard tribes have also resided in the jungles of Cambodia

near the border of Vietnam’s Central Highlands, the border having been drawn by the French during their occupation.

Accordingly, CIA directed that cache sites would be established by the Jerai and the U.S would willingly supply these caches

until 1975 for the inevitable war to come.

It was not uncommon for an entire Montagnard company to return from patrol completely naked, without weapons or munitions.

We would simply notify CIA that we needed re-supply for 200 fighters which would arrive the next day by the number of C-130’s

required to bring in the required equipment which would then be presented to the son of the leader of the Fulro Movement who

just happened to be one of our company commanders.

This military arsenal was later used by the Fulro Movement in the 1980’s when their objectives were focused on Hanoi

who were then in the process of attempting to eradicate the Montagnard Tribes.

During the same time period, 1956, when the South Vietnamese Government was not quite two years old, CIA used it’s

secret ‘proprietary’ airlines, Air America and Continental Air Transport, CAT, as well as numerous contracted

ocean going vessels to import 1.1 million North Vietnamese Catholics to shore up the Diem Regime who was having trouble with

the majority Buddhist population. Repressive measures taken by the Diem Regime against the Buddhist’s resulted in rioting

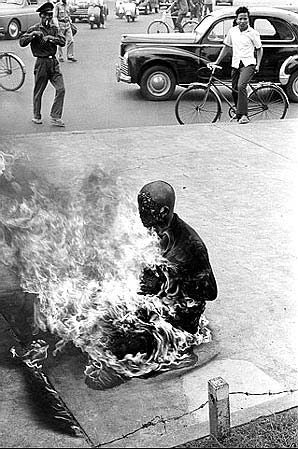

and self immolation in the streets of Saigon in protest which caused international uproars over the American backed Diem.

Then, on June 11, an aged Buddhist priest, Thich Quang Duc, sat down at a major intersection, poured gasoline on himself,

took the cross-legged 'Buddha' posture and struck a match. He burned to death without moving and without saying a word. Thich

Quang Due became a hero to the Buddhists in Vietnam, and he dramatized their cause for the rest of the world.

|

Saigon, June 11, 1963

| "I was to see that sight again, but once was enough. Flames were

coming from a human being; his body was slowly withering and shriveling up, his head blackening and charring. In the air was

the smell of burning human flesh; human beings burn surprisingly quickly. Behind me I could hear the sobbing of the Vietnamese

who were now gathering. I was too shocked to cry, too confused to take notes or ask questions, too bewildered to even think….

As he burned he never moved a muscle, never uttered a sound, his outward composure in sharp contrast to the wailing people

around him."

- David Halberstamm, NY Times

|

Saigon, October 5th, 1963

|

Right picture:

Passers-by stop to watch as flames envelope a young

Buddhist monk, Saigon, October 5th, 1963. The man sits impassively in the central market square and has set himself on fire

performing a ritual suicide in protest against governmental anti-Buddhist policies.

Thousands of Buddhists fled the capital and eventually joined the Resistance. Those displaced by this massive importation

became the seeds for the upcoming Viet Cong, VC revolt and the ensuing “Vietnam War”. Vietnam had never been a

democracy and would begin its twenty one year reign as a dictatorship and eventually succumb to the North Vietnamese forces

on April 30, 1975. So much for political and military intervention to place “democracy” in a land that had no

desire for it or the “domino theory”, the American excuse for the ‘assistance’ to the new Vietnamese

Republic’ in the first place. Unfortunately, the Americans refused to pay attention to the lessons learned by the French

during the Indo-China War. During the Vietnam War the same mistakes were made and the Americans paid a high price for them,

eventually withdrawing as the French did in 1954 after the battle of Dien Ben Phu.

President Diem (pronounced Ziem), had been living in exile from the Bao Di State of Vietnam which had political control

before the 1954 end of the French Indo China War. Diem had been quietly living in a Catholic Convent in the State of New Jersey

before he was plucked out of obscurity by the CIA, with the approval of the Vatican, and imposed as the leader of the

new South Vietnam, created by the Paris Peace talks and the United Nations in 1954.

Project Omega

In late August and September of 1967, Project Omega was working a jungle area called Plei Trap, known to be a transit and

staging area for North Vietnamese Army (NVA) forces operating further south. Plei Djereng was Project Omega’s Forward

Operating Base (FOB) and its adjacent airfield constructed of Pierced Steel Planking, PSP, served for air operations, medevac

and C-130 re-supply.

Plei Trap is a valley between a range of north-south mountains approximately 40 miles in length with a number of rivers

and streams running predominantly north-south. The terrain was rolling and largely heavily wooded with double and triple canopy

jungle which added to the confusion of topographic recognition for those using maps on the ground. There were also located

occasional open areas used as landing or evacuation sites when the situation permitted. Otherwise, air operations were used

to blow holes in the overhead canopy but mainly for emergency or “hot” extraction of small recon teams. The North

Vietnamese Army, NVA, trails ran also north-south and were wide enough to drive a jeep sized vehicle on, at that time, with

bridges and well-defined tracks not discernable from the air. Therefore, the only accurate account of enemy movement through

the large area would be accomplished by men on the ground operating on foot. They would be inserted by helicopters which would

land in those areas where gaps in the jungle canopy existed. Upon landing the relatively small reconnaissance teams of five

to seven men would melt into the eternal darkness of the jungle.

During 1967, Project Omega was operating under strength with only six of the authorized nine Reconnaissance Teams (RT’s)

consisting of two U.S Special Forces and four indigenous team members. Though authorized nine “Roadrunner” teams

(four indigenous dressed as VC or NVA who roamed the trails acting their parts), we didn’t have any organized at that

time. There were three backup Mike Force type companies of three hundred each led by U.S Special Forces members. Assigned

were two USAF FAC’s, two Army Helicopter Gunships, C Models armed with two Gatling type six barrelled machine guns each

of which could fire six thousand rounds a minute, and four “Huey” helicopter transports, H Models (slicks).

In addition to Omega, there were other “Greek” Projects; Delta, Sigma and Gamma. Delta was the original “recon”

organization of the Projects and was the forerunner of Delta Force of today’s Special Operations Command. Sigma was

closely associated with MACVSOG and used similar tactics and personnel in their operations. Gamma, which has no written history

available to the public, to date, used photos in its ground floor headquarters called The Hotel, displaying Special Forces

Civic Action projects to hide it’s true structure and mission; Gamma was located in a six story building in downtown

Saigon and staffed with Military Intelligence, MI, (misnomer) personnel pretending to be and wearing Green Beret’s and

Special Forces Insignia to hide their MI affiliation. Deeper, the MI officers coordinated the activities of Cambodian elements

whose Top Secret missions originated in the U.S Embassy and the CIA.

The mission of Project Omega was “To locate but not engage hostile forces operating on the Cambodian/South Vietnam

Border”. An exception to this mission order was to capture alive or “body-snatch” a North Vietnamese Army

Courier if practical. Such terms as body-snatch are vernacular of and for CIA operations. It translates to Kidnapping.

Early in September 1967, RT #7 was briefed for an operation in the Plei Trap inside the operations tent abutting the airstrip.

Reduced to five in number the team leader (O1 in reconnaissance) was Sergeant First Class Kenneth Carpenter and his second-in-command/radio

operator was (O2) Sergeant First Class Jerry (“Mad Dog”) Shriver, listened intently to the update on the enemy,

weather and terrain. More rainy weather (from the eastern monsoon) was predicted. Other teams recently extracted from the

same general area reported numerous trails, streams and elevations changes not indicated on any available map and the enemy

was what the team must locate without revealing their own presence. The three smaller, darker, black-eyed members of Recon

Team 7 listened intently as well. (Because of our short staffing at Project Omega, Carpenter, Shriver and their Montagnard’s,

were “on loan” from Forward Operational Base (FOB) #1 in Kontum, some thirty miles north, and were members of

Military Assistance Command Vietnam Studies and Observation Group, MACVSOG, CCS, Command and Control-South, whose primary

work areas were inside Cambodia. Because the U.S military in Vietnam had no operational jurisdiction into Laos and Cambodia,

these SOG operations were controlled and directed via the CIA, and the MACV designation was a “layered” misnomer

for security reasons although any mention of MACVSOG was in hushed tones and required Top Secret clearance to discuss at any

level.

(This pretext was not to prevent the NVA or VC from knowing that US Forces were operating in Cambodia and Laos, as they

had killed or been killed by SOG operations for years; it was to prevent American citizens from knowing that US Forces were

operating outside of South Vietnam. The political uproar would have had curtailing effects on the entire war effort, or in

the vernacular of the military, exposure of SOG would “seriously effect the further prosecution of the war”.)

The team then moved to the area of the helicopters. The gunships cranked up first while the turbine engines screamed as

the rpm’s increased. Then the two main rotor blades slowly developed speed and matched the powerful pitch as quick metal

cut through the damp air. The “guns” backed out of their respective revetments and then moved clumsily across

the taxi way on their skids to the main strip pointing due west to Cambodia just 13 miles away.

Carpenter positioned his three Montagnards on the floor of their transport helicopter. The whine of the turbine reached

its peak as Shriver finished retching and wiped his face on his sleeve. The pilots had seen Shriver retch many times before

and knew that once the queasiness took its course, he was ready.

All of the team members were dressed in ‘sanitized’ clothing suited to assist in concealment and without insignia

of rank or nationality. Each member wore a head scarf, fitted snugly around the contours of the head which was used to obscure

the facial features from recognition by enemy forces. Additionally, all were painted with camouflage stick for concealment

purposes. All were armed with AK-47 assault rifles and 9mm pistols. Shriver carried an AK-47 and an SKS Rifle and a small

pistol in an ankle holster. Shriver climbed up into the helicopter and took his seat next to the door gunner. Thumbs up all

around and the infiltration was underway with six choppers taking off “in trail”, one behind the other until reaching

three thousand feet where they would fly in a formation with the slicks side by side and the guns bringing up the rear.

The H Model Hueys, lighter and with more powerful engines, easily leaped straight up after “pulling power”,

clearing the sandbagged walls of the revetments as they swung off to the west, soon to be joined by the heavy, lumbering guns.

The United States Air Force Forward Air Controller (FAC) had been on station for 40 minutes, some ten miles from the planned

insertion site and several valleys away. Flying his fixed-wing Birddog (Cessna 0-1F/G) in irregular patterns above 7000 feet,

he provided an airborne radio link for the deployed teams and also assisted in the infiltration by guiding and talking the

choppers, flying at treetop level and hugging the terrain, into the planned site. The team leader had flown with the FAC the

previous day to search for an infiltration site near the area to be reconnoitered. Now the team leader relied on the FAC to

guide them to their destination.

The choppers would fly the same course, 20 seconds apart, in trail. A normal sequence would have a gunship fly over the

LZ followed by the chopper with the insertion team. This allowed time for the team to offload the chopper at the planned landing

site as another chopper would pass overhead, enabling the insertion chopper to climb up and follow the same fight pattern

among the other choppers. Another “slick” would then over fly the LZ and continue, then another followed by one

of the gunships. All would follow an erratic pattern with several other simulated landings until they cleared the landing

site by some distance, then gained altitude and waited for the “all clear” signal from the inserted team. This

signal to the FAC was whispered into the team’s radio or a designated number of hits on the push to talk (squelch) button

would be used to signal the FAC that all was well.

The reason for maneuvering in this manner was to deceive and confuse any enemy forces that might be in the area as to the

team’s exact landing location. Although the sound of the turbines and the “pops” of the rotor blades were

audible over and along the line of flight, detection of the exact landing zone (LZ) was difficult at best because of the noise

of the helicopters, one after another seemingly on a low level flight over the area. Visibility was extremely limited due

to the dense jungle growth. Unless a team was inserted directly upon or very near enemy forces, the insertion would generally

be uneventful, though the enemy tended to check out all possible LZ’s. But one never knew, and that was Shriver’s

dilemma. Eighty-two missions in seven months had taken its toll on that very brave and dedicated soldier! Most missions were

scheduled for five days unless the infiltration site was “hot”, occupied by enemy. In that case, the team was

immediately extracted, usually under fire. Missions were counted regardless of the duration. A five day mission could be shortened

at any time due to discovery by enemy forces or the opportunity to “snatch” an NVA Courier.

The team moved quickly but quietly in a prearranged direction for a specified distance, in this case, 400 meters from the

LZ. Carpenter thumbed the transmit switch twice, waited two seconds, and pressed twice more. The unmistakable clicks told

those listening in orbit eight miles away that all was well—no enemy contact. The helicopters then returned to Plei

Djereng while the FAC flew a lazy pattern 7000 feet above an adjacent valley, listening for action messages from the team.

RT #7 had been given the additional mission: “Body Snatch” (abduction of a prisoner). A wealth of knowledge

and information relating to the current enemy capabilities could be obtained from a captured soldier. Information/intelligence

gained by previous insertions into the general area could be confirmed and updated with the successful “Snatch”

if the opportunity presented itself. Hopefully, the prisoner would be from the North Vietnamese regiment believed to be operating

in the Plei Trap Valley although there was an almost constant flow of replacements, supply convoys and couriers for units

operating further south. If from the Plei Trap NVA regiment, the prisoner might provide information necessary for offensive

action by large-scale American Forces such as the 4th Infantry Division in whose operational area we were conducting our missions.

Ken Carpenter and Jerry Shriver had been issued .22-Caliber Ruger Mark 1 manufactured semi-automatic pistols equipped with

silencers. Previous “Snatch” missions had been successful in capturing enemy personnel but all had died before

interrogation due to shock and blood loss from the inherently massive wounds inflicted by CAR-15 bullets, a shortened stock

modification of Colt’s M-16 .223-Caliber Rifle. The .22 Ruger was used in hopes of disabling but keeping the prisoner

alive for interrogation. (CIA quickly responded to our request for these pistols which were flown from the Agency’s

Okinawa storage facility to Vietnam).

Darkness fell rapidly in the valley. Thirty minutes after landing at dusk, the team moved quickly but quietly to their

assigned area of operations which was designed to overlap areas of previous missions. This would facilitate confirming or

updating previous intelligence gathered by earlier forays into the Plei Trap. There they spent the night back to back in two

groups: Shriver with one of the Montagnards, Carpenter with the other two.

Morning broke with the fog and low clouds hanging in the trees. Only the bottom of the thirty foot canopy was visible.

The sixty and ninety foot tree tops were not in sight. The triple canopy layer of trees not only obscured the team from air

observation, it also greatly diminished the amount of light that was filtered through the jungle canopy. Carpenter clicked

twice on the transmitter and received three clicks in reply from the FAC who had arrived on station ten miles away.

The team moved through their area of operation, AO, looking for a trail and a vantage point from which to observe it. After

forty-five minutes of movement a trail was located and the team split; two on one side of the trail and three on the other,

each 20 feet off a well beaten path. Three hours later, though the sun burned down on the top of the jungle, the fog still

hung in the lowest canopy as three Vietnamese, laughing and joking, walked past the team on the trail.

Carpenter looked across the trail at Shriver and saw him slowly shaking his head indicating “no”. Carpenter

remained in place and the three Vietnamese were soon out of sight. Three minutes later, 75 heavily armed North Vietnamese

passed by the hidden team. Shriver had a sixth sense about such matters and Carpenter was glad of it.

Two hours passed and a light drizzle began to fall as Shriver came alert. He had been listening intently while observing

a trail of ants moving their eggs along the ground in front of him. All the team members could hear the talking now. Two North

Vietnamese, one carrying a rucksack and a pistol on his hip, the other with a rifle slung across his back, walked down the

path toward the split team. They were moving in the same direction as the previous groups.

After deciding to take the courier prisoner, Shriver squeezed off a shot from his .22 hitting the lead soldier behind his

left ear. As the man sprawled dead, face down on the trail, the other stopped, looked at his fallen comrade, then up at Shriver,

who quickly pumped two shots into the man’s left thigh. As he crumpled to the ground, Carpenter moved over him and swiftly

administered two quarter grain surrettes of Morphine. The prisoner was gagged, searched, handcuffed and on Shriver’s

shoulder in less than a minute. Meanwhile the Montagnards searched the dead soldier, removing his rifle, booby trapped the

body with two grenades which had the delay fuses removed to insure instant detonation and placed two claymore mines on nearby

trees at shoulder level with trip wires laid on either side of the trail. The deadly trap would ensure time and distance from

possible pursuers. This relatively silent maneuver would serve to give no notice to other individuals who were surely using

the same pathway. They would only sense danger when coming upon and observing the dead soldier on the trail.

The team moved their prisoner northwest toward a prearranged ex-filtration site two kilometers distance. Their trek was

on a compass heading and used no trails to get to the objective. The Montagnards covered the path left by the team and naturally

covered any plant displacement created by the team. Chances were that they would not be tracked. Carpenter paused after ten

minutes and keyed his radio to gain the attention of the FAC. After establishing contact, Carpenter whispered “onion”

into his radio microphone, the codeword for “Body Snatch” success, and the team then moved to the extraction LZ.

Thirty minutes elapsed when the team heard the unmistakable explosion of two grenades followed shortly by the “crump”

of one of the claymore mines. Explosives give a distinguishable audio ‘signature’ when they detonate and this

knowledge allowed the team to determine that their Claymore mines had indeed gone off as planned. Chances were favorable that

the injuries and death inflicted at the “Snatch” site would deter any immediate search for the team. Nine more

minutes passed as the team arrived at the clearing for the ex-filtration and the FAC had called for the choppers to lift the

team and their prisoner from the Plei Trap and back to Plei Djereng.

The prisoner was treated for his wounds, bathed, fed and given clean clothing. His rucksack contained 217 letters from

North Vietnam to members of the NVA regiment, promotional orders and various assignment changes but nothing of “operational”

interest. The prisoner, although still groggy and giddy from the Morphine injections, told of his walk from Hanoi, down through

Laos and into South Vietnam. The 75 NVA soldiers who preceded him on the trail were replacements for the regiment to which

the mail had been destined.

That information necessitated another insertion into the Plei Trap valley. A fresh team was alerted and the process of

preparing another mission began.

RT #4 was headed by Master Sergeant Bob Price and Staff Sergeant John Miller.

Their mission was to locate, observe and identify elements of the NVA regiment in the valley so the 4th Infantry Division

could airlift forces in to engage the NVA regiment in battle. Bob Price then flew with the FAC to locate and mark an infiltration

site ten kilometers south of the last contact made by RT #7.

Later the next afternoon, RT #4 boarded the same choppers and flew into the previously reconnoitered LZ. As the team left

the chopper, they noted a gunship flying close overhead and firing it’s mini-guns. The team immediately noticed an NVA

regimental combat flag flying from a newly stripped tree. The worst possible situation had come to bear as the team realized

they had landed in the midst of hundreds of NVA who were maneuvering for direct action to kill or capture the team.

Voices cracked in the clear over the radios. “….shit, they’re everywhere. Get us out!”

“Wolfpack Six, this is Three, I am going in to get them….”

“Roger that, Three. The guns will be raking east to west where most of the activity is. Have the team try for the

next clearing two seven zero from their present locale.”

“Bring in the guns, now!

“Roger three, they’re on the move now.”

“I have two F-102’s three minutes out and will have them put some steel between the team and the NVA”,

radioed the FAC.

“Roger that” radioed Three. “Ask ‘em to kick in their afterburners!” We need them now!

“On the way, wait!” came the reply.

The two gunships lined up for a pass as Price threw a green smoke grenade.

“Give it hell east of my smoke”, he spoke into his radio.

“Roger. I see green.

“You got it.”

The gunships arced in as their mini-guns spewed forth thousands of rounds and rockets swished toward the targets. The “slicks”

circled clear waiting for a chance to dart in and recover the team.

“Fast Movers are here. Where do you want them?”

Price through another smoke grenade: “East of my smoke and a tad north, replied Price.

“I see yellow” said the FAC.

“You’ve got it,” yelled Price.

(If the team on the ground announced the color of the smoke grenade in advance, the enemy may also throw a number of the

same color. This tactic was used to prevent confusion and duplicate action by a listening or observing enemy force.)

The FAC guided the F-102 Delta Daggers into the action and they dropped a 200 pound bomb apiece.

“How’s the placement”?

“There’s shrapnel everywhere. I love it! Keep it in the trees…right there…that’s right…keep

it coming….there are at least forty of ‘em in the trees….one more pass and we can move in the choppers….this

is gonna be hot! Have the guns hit the stream on the north boundary to the clearing. There are six zero to seven zero moving

into position now!”

The FAC guided the jets in again and again to drop more 200 pound bombs and had the gunships strafing their mini-guns in

between passes and on the stream bed.

The scream and roar of the jets and helicopters melded with the explosions of the bombs and rifle fire with the welcomed

machine gun fire from the guns. The odor of war was everywhere.

Finally, after the enemy fire was suppressed, the insertion chopper landed in the LZ as the team rushed to get aboard firing

their rifles on automatic behind them. Then the air was again filled with the crack of bullets as the team scrambled aboard.

Two bullets thudded into the tail boom of the chopper as the pilot pulled pitch and lifted off. The guns continued to rake

the area as Wolfpack #3 cleared the LZ and gained altitude. Amazingly and miraculously, no one on the team or chopper crews

was wounded. Quick reaction by the air power available, both Army and Air Force, is credited for a superb team effort in the

face of heavy gunfire.

As the choppers landed and commenced refueling, the FAC landed and ran over to me as I emerged from the H-Model Command

and Control “slick”. The commander of Project Cherry was on R & R at the time and I commanded in his absence.

“Captain Mac, there are hundreds, perhaps six or seven hundred North Vietnamese running around the site we just left.

This is perfect for a B-52 strike. The Air Force has one on the way to North Vietnam right now, but we can certainly justify

diverting the strike if you give the okay”. On his previous tour in Asia, our FAC had been a B-52 ‘driver’

and was really enthused about seeing this part of the action up close and personal.

I approved and the request was sent via the Air Force communications channels and the B-52 Arc Light was diverted to our

‘target of opportunity’. The target coordinates were radioed through the 7th Air Force channels with justification

for a “target of opportunity”. The B-52 mission was immediately approved and made ‘in midair’.

The Air Force recommended an impact area 1000 x 3000 meters to be laid down by five B-52 bombers, flying in a three-plane

Vee formation followed in trail by two bombers abreast. They would release their iron bombs from 35,000 feet. Each bomber

carried one hundred and ten 750 pound bombs, internally and on wing pods. There would be three passes made, each B-52 dropping

one third of it’s payload per pass. High accuracy was insured because SKY SPOT guidance was used by beacon radar ground

stations placed strategically throughout Vietnam utilizing triangulating techniques to guide the bombers over a release point

that was calculated to place the bombs on target, day or night, rain or shine. Overall, 550 individual 110 pound bombs would

saturate the target with fuses set to go off above, on or under the ground by delay fuse, in an appropriate mix. The above

ground detonations, called “Daisy Cutters” spread shrapnel in all directions for 300 to 400 meters virtually cutting

down any human and most jungle growth in its path. The bombs set for detonation at ground impact created very large craters

and shock waves that tumbled the jungle. The delayed bombs sank into the earth prior to exploding thereby collapsing tunnels,

storage facilities sleeping quarters, munitions storage sites and hospital areas. The hospital facilities were not purposely

targeted but we had no way in advance to identify them. Those engaged in wars know that ‘shit happens’ that you

have no control over. That realization comes with the territory and the profession.

An hour later, shock waves blasted through the air as bombs exploded with the rapidity of a string of firecrackers but

with the cumulative force of over 412,500 pounds of TNT. The jungle canopy was gaping and torn; huge trees tumbled in slow

motion in the air as wave upon wave demolished and scarred the jungle. Blast waves rippled and joined as the bombs erupted.

Then the delays would erupt with sporadic frequency further adding to the mix of hell and carnage.

Each Arc Light in South Vietnam called for a Bomb Damage Assessment, BDA, team to make a ground reconnaissance of the target

area to assess casualties, accuracy, damage to enemy forces and to make recommendations for further strikes, if needed.

As the B-52’s made their final approach to the target area, an Omega BDA team watched from their hovering choppers

four kilometers away and saw the massive, total destruction of the target. It would be difficult to imagine surviving such

an attack. The choppers were at 3000 feet waiting for the signal to move in and land.

The dust was spiraling and rising past 15,000 feet as the FAC gave the word that the last bombs had indeed detonated and

the choppers moved into the broken, twisted target area that had been verdant jungle only minutes before.

Two choppers hovered over a large bomb crater and slowly moved to the rim to deposit elements of the BDA team. No sooner

had they landed when the team came under intense, grazing interlocking machine-gun fire.

The FAC ordered in fighter-bombers, on call in the distance, and the Army gunships went to work on the target area directed

by the BDA team. Jets were then brought in at high angles to deliver bombs and then cannon fire which consisted of 20mm with

exploding mini-warheads. The fight was on but the decision was made to extract the BDA team and try again the next day. It

was dark by the time the choppers and FAC landed at Plei Djereng.

That night, the members of Omega, including the FAC’s and chopper pilots, attempted to analyze how anyone or anything

could survive a bombing as concentrated and massive as the Arc Light strike was that day. A tale was related of an Arc Light

strike in III Corps of Vietnam (immediately north of Saigon, now Ho Chi Minh City, in an area designated as War Zone D. The

strike had inadvertently caught four members of an “A” Company, 5th Special Forces Group, “Road-Runner”

team in and under the Arc Light mission. After the strike, a BDA team flew in to find all four roadrunners madly waving their

neckerchiefs, standing in the midst of massive bomb craters—none was as much as scratched, though all were deafened

and bruised from being buffeted by near misses. But no one could remember a case where an entire enemy fighting force rose

from the target area like the mythical Greek warriors from a dragon’s seed to put up a coordinated and determined resistance.

Another BDA attempt in daylight the following morning should provide some answers to the dilemma.

During the night, Omega and MACVSOG Recon Teams’s deployed adjacent to the target area reported mass movements out

of the area and across the “nearby” Cambodian border. Eleven different sightings of over 100 enemy troops each

were observed and plotted by “trail watch” teams deployed on both sides of the border. Specially equipped Army

Mohawk aircraft with side-looking radar (SLAR) and the capability for infrared photography also reported and documented mass

movements to the west from the target area and other areas surrounding the zone. It became obvious that a large number of

the enemy in the target area had survived and had displaced to the “neutral” territory of Cambodia to lick their

wounds and prepare for action on another day.

The next morning the BDA team landed in the target area without a hostile shot being fired, though there was plenty of

airborne firepower on call nearby, if needed. The team searched and recovered assorted weapons, many twisted and inoperable,

including crew-served, two or more required to operate, weapons found only in units at North Vietnamese division level. It

became apparent that a large unit, including at least some divisional strength attachments, had been assembled at that point

in the Plei Trap valley—perhaps in preparation for an attack on the U.S 4th Infantry Division headquartered in Pleiku.

There would be no reason for the presence of such a large unit as only insignificant sized units were located between them

and the 4th Infantry Division. An NVA Division normally contained 13,000 men and women.

A few bodies were recovered and parts of bodies were resurrected from hastily dug graves where they were buried by the

NVA survivors. Massive blood trails, indicating many wounded, led west into Cambodia.

Discovery:

The most startling discovery was the means by which those who survived to fight the BDA team had remained alive and effective.

Carved into the side of a hill was a bell shaped room, partially exposed by one of the 700 pound bombs. The room was designed

to capture the vibration from the sounds of the B-52’s engines high off in the distance which caused the room to “hum”

or reverberate. That ingenious early warning device allowed time for the enemy to be notified by radio and seek sanctuary

in numerous caves and tunnels dug into the staging and assembly area. Although some of the underground refuges were destroyed

by direct hits, many more were not, allowing the survival of 50% or more of the force. The speed of the approaching B-52,

normally flying at 650 mph, had to reduce speed in order to open the bomb bay doors. But the sound of their engines traveled

at the speed of sound, 750 mph and allowed for immediate action on the part of the NVA to survive the upcoming massive bombing

by Arc Light missions. This differential caused the “bell room” to hum long before the B-52’s dropped their

first bombs!

Ingenuity:

We were struck with the realization that our most sophisticated non-nuclear bomb delivery system was negated by a series

of holes in the ground.

The initial deductions concerning the function and effectiveness of the bell chambers were later confirmed by enemy prisoners.

Thus an Omega RT and BDA team stumbled upon a primary example of NVA ingenuity and field expediency against the high-technology

techniques of strategic saturation pinpoint bombings of Strategic Air Command’s heavy bombers.

The bold recon men of the Special Forces reconnaissance projects figuratively tipped their Green Beret’s to a professional

and gutsy enemy.

I filed an after action report to General Rosson on the details of the above. I was transferred to another CIA directed

unit shortly thereafter and was not privy to any modifications as a result of our findings.

Epilogue:

The B-52 Arc Light missions during the Vietnam War not only dropped bombs. They also made “leaflet drops” in

enemy controlled areas. An example of the messages of these propaganda efforts by the USAF follows. Both sides in the war

employed (effective) propaganda.

“This is the mighty B-52. Now you have experienced the terrible rain of death and destruction its bombs have caused.

These planes come swiftly, strongly speaking as the voice of the Government of Vietnam proving it’s determination to

eliminate the Viet Cong threat to peace. Your area will be struck again and again but you will not know when or where. The

planes fly too high to be heard or seen. They will rain death on you again without warning. Leave this place to save your

lives…..”

On January 30th, 1968, the TET Offensive began all over South Vietnam’s major and minor cities including all major

U.S. military installations, including Saigon. On one of these military installations located at Long Binh, 25 miles north

of Saigon, NVA commando teams targeted the Field Grade Officer’s, (major and above), BOQ, with the intent of taking

ten to twelve prisoners, alive. All 25 of the commando’s were killed during their attempted assault. During subsequent

body searches of the dead, notes in English were found on each of the commandos.

“Come with us. You will be treated well. You have nothing to fear except B-52’s.”

This was the first recognition of the absolute terror inflicted by the B-52 Arc Light missions.

The first B-52 mission during the Vietnam War took place on June 18, 1965 when twenty seven B-52 bombers flew from Guam

to Vietnam and dropped 750 and 1000 pound iron bombs on a suspected VC stronghold from 50,000 feet altitude. Results are unknown.

Nixon and Kissinger’s illegal secret bombing:

Later in the war beginning in 1969, the secret bombing of Cambodia began which was ordered by Nixon and Kissinger to hide

the fact from the Congress and the American People, B-52 flights departing Guam and Okinawa would undergo in-flight changes

to bombing targets originally selected for drops in South Vietnam according to flight briefings prior to take off. Upon reaching

the designated altitude the flight leader would open a Top Secret envelope which provided new coordinates for the target.

Only the flight leader and his navigator were privy to the modification of the new target inside Cambodia. The rest of

the flight of B-52’s would follow the flight leader without question. This ruse was established to prevent unauthorized

leakage of the secret bombing of Cambodia. There were 3000 such flights which secretly bombed Cambodia between February, 1969

and June, 1972, the end of the U.S involvement in the Vietnam War.

Almost as a sad side note, there were recurring complaints within the US Air Force that the supply of 750 bombs was

critically low in the bomb inventory and no one could figure out why 330,000 bombs were missing. Nixon and Kissinger has to

resort to politely but quietly asking our allies to return a portion of their own inventories originally supplied by the USA

in order to sustain the Top Secret massive bombing of vast portions of Cambodia.

Those fight leaders who later retired maintained their silence about these missions merely stating, “What I learned

in the Air Force, stayed in the Air Force.”

Jerry Shriver went Missing In Action, MIA, in April, 1969. Reports from his team members indicate he was wounded at least

four times during a firefight on a MACVSOG mission inside Cambodia. He remained on the MIA list for many years, promoted to

Master Sergeant, and finally listed as Killed In Action, KIA, Body Not Recovered, BNR.

SFC Jerry M. "Mad Dog" Shriver was a legendary Green Beret. He was an exploitation platoon leader with Command and Control

South, MACV-SOG (Military Assistance Command, Vietnam Studies and Observation Group).MACV-SOG was a joint service high command

unconventional warfare task force engaged in highly classified operations throughout Southeast Asia. The 5th Special Forces

channeled personnel into MACVSOG (although it was not a Special Forces group) through Special Operations Augmentation (SOA),

which provided their "cover" while under secret orders to MACVSOG. The teams performed deep penetration missions of strategic

reconnaissance and interdiction which were called, depending on the time frame, "Shining Brass" or "Prairie Fire" missions.

On the morning of April 24, 1969, Shriver's hatchet platoon was air assaulted into Cambodia by four helicopters. Upon departing

the helicopter, the team had begun moving toward its initial target point when it came under heavy volumes of enemy fire from

several machine gun bunkers and entrenched enemy positions estimated to be at least a company-sized element.

Shriver was last seen by the company commander, Capt. Paul D. Cahill, as Shriver was moving against the machine gun bunkers

and entering a tree line on the southwest edge of the LZ with a trusted Montagnard striker. Capt. Cahill and Sgt. Ernest C.

Jamison, the platoon medical aid man took cover in a bomb crater. Cahill continued radio contact with Shriver for four hours

until his transmission was broken and Shriver was not heard from again. It was known that Shriver had been wounded 3 or 4

times. An enemy soldier was later seen picking up a weapon which appeared to be the same type carried by Shriver.

Jamison left the crater to retrieve one of the wounded Montagnards who had fallen in the charge. The medic reached the

soldier, but was almost torn apart by concentrated machine gun fire. At that moment Cahill was wounded in the right eye, which

resulted in his total blindness for the next 30 minutes. The platoon radioman, Y-Sum Nie, desperately radioed for immediate

extraction.

Maj. Benjamin T. Kapp, Jr. was in the command helicopter and could see the platoon pinned down across the broken ground

and rims of bomb craters. North Vietnamese machine guns were firing into the bodies in front of their positions and covering

the open ground with grazing fire. The assistant platoon leader, 1Lt. Gregory M. Harrigan, reported within minutes that half

the platoon was killed or wounded. Harrigan himself was killed 45 minutes later.

Helicopter gunships and A1E aircraft bombed and rocketed the NVA defenses. The heavy ground fire peppered the aircraft

in return, wounding one door gunner during low-level strafing. Several attempts to lift out survivors had to be aborted. Ten

air strikes and 1,500 rockets had been placed in the area in attempts to make a safe extraction possible. 1Lt. Walter L. Marcantel,

the third in command, called for napalm only ten yards from his frontline, and both he and his nine remaining commandos were

burned by splashing napalm.

After seven hours of contact, three helicopters dashed in and pulled out 15 wounded troops. As the aircraft lifted off,

several crewmen saw movement in a bomb crater. A fourth helicopter set down, and Lt. Daniel Hall twice raced over to the bomb

crater. On the first trip he recovered the badly wounded radio operator, and on the second trip he dragged Harrigan’s

body back to the helicopter. The aircraft was being buffeted by shellfire and took off immediately afterwards. No further

MACV-SOG insertions were made into the NVA stronghold. Jamison was declared dead and Shriver Missing in Action.

On June 12, 1970, a search and recovery element from a graves registration unit recovered human remains that were later

identified as Sgt. Jamison, but no trace was found of Shriver.

For every insertion like Shriver's that were detected and stopped, dozens of other commando teams safely slipped past NVA

lines to strike a wide range of targets and collect vital information. The number of MACV-SOG missions conducted with Special

Forces reconnaissance teams into Laos and Cambodia was 452 in 1969. It was the most sustained American campaign of raiding,

sabotage and intelligence-gathering waged on foreign soil in U.S. military history. MACVSOG teams earned a global reputation

as one of the most combat effective deep-penetration forces ever raised.

The missions Shriver and others were assigned were exceedingly dangerous and of strategic importance. The men who were

put into such situations knew the chances of their recovery if captured were slim to none. They quite naturally assumed that

their freedom would come by the end of the war. For 591Americans, freedom did come at the end of the war. For another 2500,

however, freedom has never come.

Since the war ended, nearly 10,000 reports relating to missing Americans in Southeast Asia have been received by the U.S.,

convincing many authorities that hundreds remain alive in captivity. Jerry Shriver's friends claim they heard on "Hanoi Hannah"

that "Mad Dog" Shriver had been captured. They wonder if he is among the hundreds said to be alive today. If so, what must

he think of us?

Ken Carpenter was reported killed during a bar fight in Alaska after he retired from the Army.

"I predict to you, that you will, step by step, be sucked into a bottomless military and political quagmire." - President

DeGaulle to President Kennedy - May 1961.

The New York Times

Vietnam's 'Lost Commandos' Win Battle

By TIM WEINER

Published: June 20, 1996

Seeking to heal a wound from the Vietnam War, the Senate voted today to give up to $20 million to the "lost commandos,"

hundreds of Vietnamese secret agents written off as dead by the United States after being dropped behind enemy lines.

The bill, which passed without opposition, calls for $40,000 to be paid to each of the commandos or their survivors. There

are at least 281 commandos known to be alive; some spent 20 years or more in prison camps in North Vietnam after being declared

dead by the United States military.

For the survivors, the payment represents roughly what they were seeking in court: $2,000 a year in back pay for their

prison time.

They are among nearly 500 Vietnamese trained by the Central Intelligence Agency and the United States military and sent

on one-way missions into North Vietnam. Some were killed immediately; most were captured, and Radio Hanoi announced that many

had been tried for treason and imprisoned. The United States nonetheless listed the living as dead, paid small amounts to

their families and buried their files under the seal of secrecy.

Seventeen commandos -- gaunt men bearing the scars of their imprisonment and torture -- appeared at a Senate Intelligence

Committee hearing today. One of them, Quach Rang, 58, who spent 23 years in prison after being captured in 1964, said in an

interview in the hearing room that he had "come back from hell" to seek justice for himself, his wife and his comrades.

The commandos sat silently as Maj. Gen. John K. Singlaub, retired, who ran the intelligence operation that sent them to

their fates from 1966 to 1968, said that the "so-called Vietnamese special commandos" were "not the responsibility of the

U.S. Government."

He said he thought some were double agents and others were really dead. Either way, each man was "declared a nonviable

asset" after his capture, the crew-cut retired Army general said.

Ho Van Son, who was 19 when he was captured in 1967, and spent 19 years in prison after the United States declared him

dead, turned to General Singlaub and said in slightly broken English, "You didn't think about what you do."

"Some leaders did not think about the men who fight for freedom," he testified. "We have to fight for our honor. The problem

is not money. No money pay for my life. But I think my honor and my friends' honor must get recognition."

The Pentagon and the C.I.A. opposed the commandos' legal request for back pay, citing an 1875 Supreme Court ruling in a

Civil War case that secret contracts for covert operations are unenforceable.

This did not sit well with the intelligence committee's chairman, Senator Arlen Specter, a Pennsylvania Republican, who

said the commandos had suffered "callous, inhumane, really barbaric treatment by the United States," which "for decades has

covered up these atrocities with classified documents."

The C.I.A.'s general counsel said the agency supported the legislation passed today as a one-time gesture, but opposed

changes in the law that could enable others who served the United States in secret and suffered for it to seek compensation.

"What about the Hmong?" said the counsel, Jeffrey Smith, reciting a list of peoples recruited by the United States for

failed military and intelligence operations. "What about the Kurds? What about the contras? What about the Bay of Pigs?"

After the hearing, two Vietnam veterans, Senator John Kerry, a Massachusetts Democrat, and Senator John McCain, an Arizona

Republican and a former prisoner of war, won a voice vote in the Senate to pay the commandos. Their measure is attached to

the overall 1997 military spending bill, which has yet to pass. The House appears likely to adopt similar legislation.

The Senators called the compensation the right way to atone for abandoning the commandos.

The United States knew it was "sending them on impossible missions with little chance of success," and after they were

captured, wrote them off as dead, "apparently to avoid paying their salaries," Mr. Kerry said.

The vote today was the first official recognition the commandos have received since their missions began in 1961. They

were mostly Roman Catholics who fled Communist North Vietnam with their families for South Vietnam in the 1950's, and were

recruited to infiltrate and carry out sabotage missions in North Vietnam because they knew its hamlets and dialects.

The C.I.A. turned the secret operation over to the military in 1964. The military abandoned it in 1970, acknowledging in

a secret report that the mission was a failure, but continuing to conceal the fates of the commandos from their families.

One reason for the failure of the operations recently became apparent: Hanoi revealed that a deputy chief of covert operations

for South Vietnam's military during the 1960's was a North Vietnam spy.

Members of the US Armed Forces ARE NOT afforded the opportunity to “seek redress” for grievances as did the

South Vietnamese Commandos. They were merely “employed” by the US Government.

There is something very wrong with this picture.

The Feres Doctrine Horror Show

APRIL 30, 1975:

North Vietnamese tanks rolled into Saigon.

One of the most famous pictures of the Vietnam War is of a tank crashing through the Presidential Palace Gates.

(Photo of tank at palace gate)

Another tank rolled down Tu Do Street in Saigon followed by trucks carrying Viet Cong soldiers starring straight

ahead.

A South Vietnamese who sympathized with the Viet Cong during the war was approached by an aquaintance who was a

French Engineer in Vietnam since 1952. "You must be pleased with this event", as they watched the parade of the victorious

march down Tu Do Street.

The South Vietnamese shook his head in disgust. "No", he said, "Those people are from the North. They

are only dressed as Viet Cong to fool the people."

Indeed, over 16,000 US had been killed during Tet and the remainder of 1968 which was the last ditch effort

on the part of General Giap with the unintended consequence to turn the war in favor of the protesters in the United States

and around the world. Therein lied his success and the ruse of showing Viet Cong entering as victors during the fall

of Saigon was only icing on the cake of deception. The Peoples National Liberation Front, the political arm of the Viet

Cong, was not in the cards for control of a united Vietnam; they were only tools of the trade and expendable assets just like

the 58,000 Americans who died in that vain war bulit on the lies of 'domino theories' and fabricated attacks on US Navy ships

in the Gulf of Tonkin.

NLF and North Vietnamese casualties reached terrifying proportions. Perhaps a half - 45,000

- of the soldiers engaged in the initial offensive were killed. What is more, they were unable to hold any of the ground they

had seized. The aim had been to spark a popular uprising in the South. When that did not materialise, partly because the communist

party was weak among urban workers, the US's superior armaments prevailed.

Years later, General Tran Do, one of the architects of the offensive, commented: "In all

honesty, we didn't achieve our main objective, which was to spur uprisings throughout the South. Still, we inflicted heavy

casualties on the Americans and their puppets, and this was a big gain for us. As for making an impact in the United States,

it had not been our intention - but it turned out to be a fortunate result."

For an American public reared on a belief in US supremacy, Tet was a shock. For three

years they had been assured that the war in Vietnam was being won. Now the disparity between US government claims and the

reality on the ground became untenable. The antiwar movement was vindicated. In the New Hampshire primary, held on March 12,

President Lyndon Johnson was embarrassed by the strong showing of antiwar candidate Eugene "Gene" McCarthy. On March 31, two