Analysis

American Violence In Iraq: Necrophilia

Or Savagery?

Part 5 of a 5-part series:

Creating our own reality

By Kim Petersen and B. J.

Sabri

Online Journal Contributing Writers

August 28, 2005—At this stage of history,

and considering the imperialist objectives of US foreign policy, wars, and interventions, and considering the history of US

atrocities in Turtle Island (North America), the Philippines, Korea, Vietnam, Iraq, and elsewhere, a question is in order:

Is the United States a torture nation?

Based on evidence gathered from America's wars in

over two centuries, the answer is a definitive yes. Trying to prove the contrary is an exercise in futility and hypocrisy.

This is for one plain reason: no one can sweep documented history under the rug and pretend it does not exist.

Maybe the US military and their civilian commanders

think that killing is acceptable in war. That is a military-industrial mindset, but the US government cannot pretend that

since the public knows it is war where killing is natural that public acceptance of it will be automatic. Since winning such

wars of conquest or aggression requires intelligence gathering, the intent is that such a permissive mindset will condone

torture. This is nonsense and its purpose is to sedate the thinking and natural anti-violence instincts that characterize

most humans.

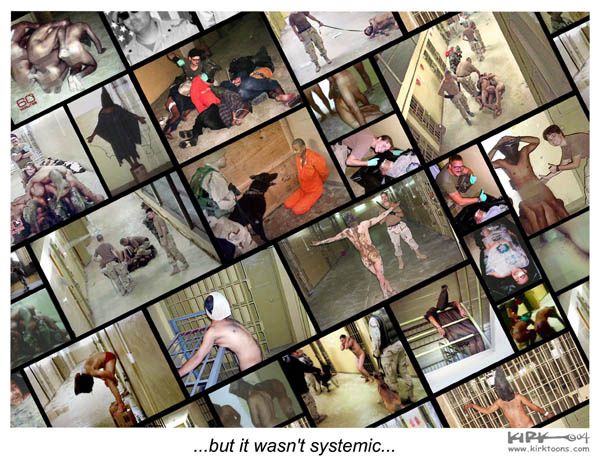

On the specific subject of violence and atrocities,

from the Korean and Vietnam Wars until present, no one can deny, there has been a remarkable sliding of the American state

into adopting torture comparable to Nazi and Israeli standards of practice. Namely, torture, rape, racial anger, religious

anger, mass murder, destruction of property, collective punishment, and disdain for established civilizations have become

institutionalized, codified, taught, and are the preferred method for putting down liberation movements, which the US and

other imperialists propagandistically call "insurgencies."

However, laying the blame solely at the feet of

the troops and the political-economic elites is an attempt at abrogating the responsibility of the citizenry to oppose war,

aggression, or occupation. Opposing wars of aggression is an individual and a societal responsibility, especially the overtly

illegal mayhem and chaos that the US has been fomenting in Iraq. One antiwar writer argued, "Because the civilian leadership

unlike the military is always indebted to public opinion for its existence, it's ultimately public approval rather than military

need that drives air war against civilians, which is why the corporate media obligingly does its bit to keep that approval

going." [1]

Nonetheless, as long as the corporate media can

dupe the public, public opinion is merely a function of media manipulation, and may never rise to claim its moral or historic

responsibility. While public approval indirectly drives war on the civilians of the aggressed nation, the directing force

behind it remains the corporate media and its connection to special interests.

While imperialist propaganda and deception portray

the United States as a victim of violence, this sense of spurious victimization must not nullify, in any way, the responsibility

of the citizenry to oppose aggressions unleashed on nations that never threatened the United States. Furthermore, it must

be conceded that it is the natural right of any country victimized by the US to oppose such aggression or occupation with

all available means.

Upholding US violence at the presidential level

is another matter. For instance, it is true that the 2004 American presidential election witnessed a media overwhelmingly

focused on the two corporate-political establishment candidates, both of who resolutely backed the violence in Iraq, while

a third antiwar contender, Ralph Nader, faced forlorn marginalization and derision. Although Americans re-elected (in what

passes for democracy in the US) a de facto war criminal to the presidency in 2004, public sentiment is not unanimous over

the invasion and occupation of Iraq and public disapproval is growing. Sadly though, this probably derives more from worsening

economic and increasing military-casualty factors, as well as a war-fatigue factor, than from a general awakening of a moral

consciousness.

One war historian held that militarism evokes public

consent through the "thrill of the process." [2] Indeed, Chris Hedges' provocative thesis is that it is through

war that humans find meaning. [3]

Of course, that is Hedges' view, but the overwhelming

fact remains that such meaning is artificial and is a product of indoctrination; and, in the end, it sanctifies war because

it is the source of emotional stability since it defines our existence by giving us meaning. This has one implication: the

patriotic fervor of war can blind one to the violent contradictions of the state and its wars. For example, the US is a state

that dissembles as a champion of human rights, and yet even it is subject to feeble criticism for running "gulags" by human

rights organizations such as Amnesty International that have become an integral part of the imperialist system. [4]

From a different angle, there are some American

intellectuals, such as the unabashed plagiarist and Zionist apologist, Alan Dershowitz, who brazenly argues for the legitimacy

of torture under circumstances of self-defense. [5] Torture, however, is not about self-defense, and has

only one purpose: extracting information from an adversary and humiliation of a portion of an occupied population. Moreover,

torture is self-defeating, being "the ultimate act of bad faith on the part of the state, and . . . therefore, credible evidence

that a state is illegitimate." [6]

Beyond that, US international violence is a means

to hide domestic issues. In fact, since President George W. Bush launched his wars, he and his regime have pursued a program

that targets and exploits the weakest members of societies—domestically and internationally—for the benefit of

elite interests. The list of regressive programs pursued by Bush and his allies is by no means short. It includes:

- Attacking social programs, dismantling environmental

protections, undermining scientific research and imperiling humanity through the granting of freer rein for industrialists

to pollute, to endanger and wipe out species, and fry the planet.

- Unleashing the scourge of war upon states opposing US

coercion, and subverting democratic processes around the world.

- Damaging the economy for a discredited ideology of empire,

gutting arm treaties, and initiating new arms races on land and in space.

- Confining the UN as international institution to irrelevancy

and, thereby, effectively abolishing the rule of international law; but, in so doing the US' own legitimacy as a state birthed

in the bloody genocide of the Fourth World has been thrust under the spotlight.

Beyond that, the US military posture around the

world and its fascist adventurism in the Middle East and elsewhere has resulted in a further beating to any lingering international

esteem to which the US was clutching. [7] But as nice as international approbation might be, it does not

motivate US policy. In 1948, George Kennan, who formerly headed the US State Department Policy Planning Staff, spelled out

the "straight power concepts" that he held should guide US policy:

We have about 60 per cent of the world's

wealth but only 6.3 per cent of its population. In this situation we cannot fail to be the object of envy and resentment.

Our real task in the coming period is to devise a pattern of relationships which will permit us to maintain this position

of disparity. We need not deceive ourselves that we can afford today the luxury of altruism and world benefaction. We should

cease to talk about such vague and unreal objectives as human rights, the raising of living standards and democratization.

Under Bush, little has changed. Journalist Ron Suskind

quoted a senior advisor to Bush saying: "We're an empire now, and when we act, we create our own reality. And while you're

studying that reality—judiciously, as you will—we'll act again, creating other new realities, which you can study

too. . . . We're history's actors . . . and you, all of you, will be left to just study what we do." [8]

It was a dismissive rejection of people power.

The late American socialist leader Eugene Debs identified

the need for a contemplative people power: "They have always taught and trained you to believe it to be your patriotic duty

to go to war and to have yourselves slaughtered at their command. But in all the history of the world you, the people, have

never had a voice in declaring war, and strange as it certainly appears, no war by any nation in any age has ever been declared

by the people."

Because war in modern times is a product of the

political, financial, and industrial elites in society, the evil scourge of war may be only debilitated if society can eliminate

the elites' war-making ability. This is a gargantuan task. For one, in a supposed capitalistic democracy, the economic elites

are the sacred cows, and their removal from power is arguably impossible without a full-fledged revolution, which is, incidentally,

an alien notion to people indoctrinated in the acceptance of the legitimacy of the state and its institutions. Therefore,

the vicious cycles of American wars, their dispensation, and the powerlessness of the people will continue until the emergence

of new or different social forces.

Still, this is an optimistic view; but can

the people halt the violence of their military forces and defeat the ideology that gives rise to such violence and

the perceived need for allocating vast human capital and financial resources to destructive ends? Considering the viciousness

of capitalist ideology, imperialism, and Zionism that dominate the United States, the systematic violence those ideologies

wreak on weaker countries as well as on the weaker individuals within their own societies, it is highly unlikely that halting

wars and violence is possible without exposing the dissenting segments of population to fierce violence from the state.

What makes change even more difficult is that while

US ideological and economic classes compete for upward mobility domestically, the elite classes compete for world domination.

At this conjecture, can the US reverse its march toward world domination and begin a program of self-rehabilitation? Barring

an unthinkable conversion of imperialist capitalism to decency and non-aggression, without sustained pressure and great sacrifice

of a huge mass of the US populace and world populace, no change in the US hegemonic ambitions will ever occur.

Thus far, and to conclude discussion on the American

violence in Iraq and elsewhere, the grim reality that faces Americans is that their society sired the evil debacle in Iraq.

In fact, despite the violence, humiliations, and perversities inflicted by the men and women serving a regime that has been

characterized as "lunatics running the asylum," many people continue to unambiguously support the troops, and, therefore,

by extension, their atrocities.

In the case of violence, separating between the

actor and his actions is a senseless preposition. American anti-imperialist Mark Twain deplored the violence of humans:

Man is the only animal that deals

in that atrocity of atrocities, War. He is the only one that gathers his brethren about him and goes forth in cold blood and

calm pulse to exterminate his kind. He is the only animal that for sordid wages will march out . . . and help to slaughter

strangers of his own species who have done him no harm and with whom he has no quarrel . . . And in the intervals between

campaigns he washes the blood off his hands and works for "the universal brotherhood of man"—with his mouth.

Currently, while warfare by imperialist choice reigns,

and while colonialism remerges as a policy of a powerful state, what can be done? There are two choices: either "we" keep

clinging to our atavistic past where violence is the motor of society, or "we" change society and ourselves.

Of course, the second is the ideal choice. Can we

achieve it?

Disparate forces, financial, economical, industrial,

ideological, theological, and military continue to shape US imperialism, its foreign policy, its interventions, and its wars.

Each of these forces, directly or by less conspicuous means, is involved in the making and application of US international

violence. The task of reversing the ideology and culture of violence that animates the US ruling classes, coupled with the

passivity, indifference, and indoctrination of the American people is by no means easy.

This combination makes a nuclear United States,

whose yearly military budget is over 400 billion dollars, the most dangerous state that has ever existed. Is that a recipe

for surrender to a colossus gone mad? The answer is no. The fate of the world does not depend solely on the United States,

but on the collective will of the world's nations. These nations can punish the United States not through military means,

but through isolation, expelling American diplomats, cutting off commercial ties, and by supporting the struggle of nations

occupied by the United States to regain their independence though military and diplomatic support. Is this utopian?

No, and the example of the Iraqi resistance that

is challenging the hyper-empire virtually alone, is the most eloquent indication that "where there is a will, there is a way."

The lack of any attempt to achieve this imposing

task of progressive change incriminates any society that unleashes violence. The same holds true conversely. Clearly, insofar

as wreaking violence is concerned, the support given by large segments of humanity for their troops to obliterate another

segment of humanity boggles any sense of morality, defies logic, and concurs only with the evil and the absurd.

ENDNOTES

[1] Lila Rajiva, "America's Downing Syndrome, or Why the Not-So-Secret Air War Stayed

'Secret,'" Dissident Voice, 22 July 2005

[2] John Keegan, A History of

Warfare (Vintage, 1993), 357

[3] Chris Hedges, War

Is A Force That Gives Us Meaning (Anchor Books, 2003), 3. "The enduring attraction of war is this: Even with its destruction

and carnage it can give us what we long for in life. It can give us purpose, meaning, a reason for living. Only when we are

in the midst of conflict does the shallowness and vapidness of much our lives become apparent."

[4] External Document, "Amnesty International Report 2005 Speech by Irene Khan at Foreign

Press Association," Amnesty International, 25 May 2005

[5] Seth Finkelstein, "Alan Dershowitz's Tortuous Torturous Argument," The Ethical Spectacle, February 2002

[6] Patricia Goldsmith, "Torture: Knowing/Not Knowing," Dissident Voice, 31 May 2005

[7] Brahma Chellaney, "The world, customized," The Hindustan Times, 13 March 2003. Prior to the

invasion, the US was warned that it "faces international opprobrium and unparalleled isolation." Phyllis Bennis, "Talking Points," Institute for Policy Studies, 5 March 2003. Some US

ideologues viewed "international opprobrium as worth the advantage of asserting the legitimacy of U.S. unilateralism once

and for all." "U.S. Image Up Slightly, But Still Negative: American Character

Gets Mixed Reviews," Pew Global Attitudes Project, 23 July 2005. The

poll of 16 countries euphemistically found that "the United States remains broadly disliked in most countries surveyed, and

the opinion of the American people is not as positive as it once was."

[8] Quoted in Tom Engelhardt, "On Bin Laden's illusions and ours," Al-Jazeerah, 23 October 2004

Kim Petersen is a writer living in Nova Scotia, Canada;

B. J. Sabri is an Iraqi-American antiwar activist. You can reach them at petersen_sabri@hotmail.com.

Source: Online Journal